The Sochi 2014 Paralympics Winter Games: My Personal Odyssey

Sochi Paralympics — Inclusive Design?

Sochi’s 2014 Paralympics Winter Games pushed the boundaries on athletic records and what differently abled athletes can achieve. As an architect involved in the preparation of the Organizing Committee of Sochi 2014’s ‘Gateway to the Future’ Paralympics Winter Games Bid, the aim was also to profoundly push accessibility barriers. Had that happened?

By SALLY SWANSON, AIA

I first walked along Sochi’s streets in 2006 as a participant on the planning and design team commissioned to prepare Russia’s International Olympic Committee bid to host the XXII Olympic Winter Games and XI Paralympics Games of 2014. At that time, Sochi was a largely nondescript coastal city on the Black Sea. Where the Olympic Park venues, Main Media Center and hotels now stand was nothing but a marshland. In the city, there wasn’t one athletic facility known for international competition and few nonnative Russians present. As I reflect back on my 2006 visit we were, without a doubt, strangers in a strange land.

By some estimates, the investments necessary to bring the existing location up to Olympic and Paralympic standards exceeded that of any previous Olympic games. Interestingly, as we now know, the Sochi Games may have been the most expensive on record, but that record has paid dividends as I’ll share with you in this report. In addition to the amount of construction necessary, Russia had also never hosted a Paralympic Games, and had passed on hosting the 1980 Summer Paralympics as they had claimed there were no athletes with disabilities in their country. The task of creating an accessible environment was not just a massive design undertaking, but also required a great deal of education, political will, and cultural change.

I had returned to Sochi on several occasions since that first time, including participating in the Russian International Olympic University Conference “Strategy of Building Barrier-Free Environment for Cities and Business” in 2012. This conference was focused on a decision-making framework to facilitate accessibility from the Paralympics Games to create a barrier-free Russia. Several years prior to the 2014 Games, I walked the streets, observing and feeling a part of this new city that was rising up amongst the old resort—airport, train station, parks and streets, hotels, and high rises. In the Village, under a fast-track construction process, were massive stadia, centers, and sporting venues. Walking up a flight of stairs in my hotel, with no elevator, I would wonder how truly accessible Sochi would turn out to be.

The 2014 Games

With great curiosity, I headed to the Games a few days before they would begin. After a long flight originating in San Francisco, which took me to New York and on to Moscow, I took the last leg towards the Black Sea. My arrival in the city of Sochi began to illustrate for me just how much work and thought had gone into creating the upcoming events.

The financial commitment and comprehensive planning reflect modern technology, a high degree of organization that surpassed many other Olympic/Paralympics events, and spectacular venues, which I attended. It is hard to give voice to the state-of-the-art facilities and incredible infrastructure—including the new roadway and the new rail system going through the mountains. The airport’s successful signage and wayfinding were positive steps towards an inclusive environment. The accessibility of the gondola infrastructure to the Rosa Khutor Alpine Center surpassed anything I had experienced.

The financial commitment and comprehensive planning reflect modern technology, a high degree of organization that surpassed many other Olympic/Paralympics events, and spectacular venues, which I attended. It is hard to give voice to the state-of-the-art facilities and incredible infrastructure—including the new roadway and the new rail system going through the mountains. The airport’s successful signage and wayfinding were positive steps towards an inclusive environment. The accessibility of the gondola infrastructure to the Rosa Khutor Alpine Center surpassed anything I had experienced.

The opening ceremony at Fisht Olympic Stadium was a phenomenal event. Having experienced the last three Paralympic Games I can say this has truly been an incredible experience. I later learned that there were 40,000 support volunteers and 10,000 paid employees all geared toward making the games a success. Friendship and support was given at every opportunity. As one might imagine the security presence was strong but not overwhelming. The organization and informational support for visitors was first class. This experience began the moment I landed and was felt throughout my visit.

The opening ceremony at Fisht Olympic Stadium was a phenomenal event. Having experienced the last three Paralympic Games I can say this has truly been an incredible experience. I later learned that there were 40,000 support volunteers and 10,000 paid employees all geared toward making the games a success. Friendship and support was given at every opportunity. As one might imagine the security presence was strong but not overwhelming. The organization and informational support for visitors was first class. This experience began the moment I landed and was felt throughout my visit.

The sense of national unity and pride in these games was touching. I was able to observe the citizens of Russia embracing the athletes, the visitors, and the Games; from the elderly grandmother to the young mother with a newborn, they had come out to support the Paralympics. The commitment and dedication to the success of this event was quite obvious. I could see signs of the vision captured in our 2006 work coming to life and given words by Dmitry Chernyshenko, President and CEO of the Sochi 2014 Organizing Committee. In his opening ceremony statement he brought this new vision to life: “Thanks to the Paralympic Games, a new era in the history of Russia has begun: one without barriers and stereotypes. The Paralympic Games have changed us; they have changed our attitude to those close to us and to ourselves. Together, we are learning to be more considerate and attentive to each other”.

The sense of national unity and pride in these games was touching. I was able to observe the citizens of Russia embracing the athletes, the visitors, and the Games; from the elderly grandmother to the young mother with a newborn, they had come out to support the Paralympics. The commitment and dedication to the success of this event was quite obvious. I could see signs of the vision captured in our 2006 work coming to life and given words by Dmitry Chernyshenko, President and CEO of the Sochi 2014 Organizing Committee. In his opening ceremony statement he brought this new vision to life: “Thanks to the Paralympic Games, a new era in the history of Russia has begun: one without barriers and stereotypes. The Paralympic Games have changed us; they have changed our attitude to those close to us and to ourselves. Together, we are learning to be more considerate and attentive to each other”.

By hosting the Paralympics, the Russian people are demonstrating their commitment to move towards justice, equality and more accessible cities. Yet bringing this vision to full fruition will take time.

Accessibility Gaps

To my surprise, as I focused on a more careful examination, it became evident that not all disabilities had been addressed. Many paths-of-travel are hazardous and often unmarked; wayfinding was not consistent and frequently confusing. There was no Braille on the signage of most of the doors, the elevator controls in many facilities were too high to reach from a wheelchair and pedestrian signage was not always clear and accommodating of varying disabilities. At the opening ceremony there was not a sign interpreter, nor were there closed captions for the deaf. Most of the events did not have closed captions for the deaf.

Despite these shortcomings, one must keep in mind the starting point. “Russia has a zero track record in terms of accessibility and they have had to get up to speed in seven years,” pointed out Craig Spence of the International Paralympic Committee. There is no doubt that they have come a long way.

Despite these shortcomings, one must keep in mind the starting point. “Russia has a zero track record in terms of accessibility and they have had to get up to speed in seven years,” pointed out Craig Spence of the International Paralympic Committee. There is no doubt that they have come a long way.

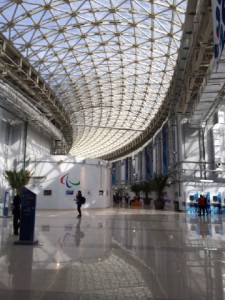

Surprisingly, in contrast to Russia’s historic track record in accessibility, I had found the airport to be very modern, well-maintained, and accessible. The wayfinding was intuitive and quite clear. The signage was simple but easily understood and included a combination of narrative and graphics (though lacking in Braille). No matter one’s physical abilities, it would be easy to maneuver through this facility.

Approaching my hotel, however, it became evident that not all facilities were going to meet the same standard as the airport. Accessibility leading to the hotel was challenged as the only ramp was placed off to one side of the main entry pavilion, sending the wrong message to those with physical limitations. The entrance to the hotel consisted of a revolving door that would provide difficulties for a wheelchair user to access, or in fact for an able-bodied individual as well. The registration counter and hotel bar were also not accessible for a wheelchair user and an excessive amount of glare was emanating from the lighting, difficult for those with visual impairments. Signage was not consistent with my airport experience, and the hotel elevator was so small that a large wheelchair user would be forced to use the service elevator; not consistent in upholding the principles of Universal Design.

Approaching my hotel, however, it became evident that not all facilities were going to meet the same standard as the airport. Accessibility leading to the hotel was challenged as the only ramp was placed off to one side of the main entry pavilion, sending the wrong message to those with physical limitations. The entrance to the hotel consisted of a revolving door that would provide difficulties for a wheelchair user to access, or in fact for an able-bodied individual as well. The registration counter and hotel bar were also not accessible for a wheelchair user and an excessive amount of glare was emanating from the lighting, difficult for those with visual impairments. Signage was not consistent with my airport experience, and the hotel elevator was so small that a large wheelchair user would be forced to use the service elevator; not consistent in upholding the principles of Universal Design.

In the disabled population, there are groups that remain disenfranchised. Accommodations for the visually impaired, the deaf, and wheelchair users were not in evidence on the exterior path of travel, and wayfinding was, in many cases, resolved at the completion of the installation and not suitable for a world-class venue. Curb cuts often seemed to be an afterthought. The pathways were not consistent, code compliance felt spotty, and dangerous changes in grade were not clearly or consistently marked. Much of this struck me as inconsistent with the high-level of organization and sophistication present throughout the games.

In the disabled population, there are groups that remain disenfranchised. Accommodations for the visually impaired, the deaf, and wheelchair users were not in evidence on the exterior path of travel, and wayfinding was, in many cases, resolved at the completion of the installation and not suitable for a world-class venue. Curb cuts often seemed to be an afterthought. The pathways were not consistent, code compliance felt spotty, and dangerous changes in grade were not clearly or consistently marked. Much of this struck me as inconsistent with the high-level of organization and sophistication present throughout the games.

Other facilities were not free of accessibility barriers as well. In one location of the Olympic Stadium, a potential tripping hazard created by a ramp had not been sufficiently addressed with handrails. At the trains in the Olympic Park railway station, the design had neglected to consider the abrupt change in level between the train doors and the boarding platform (though assistance was provided with manually-placed ramps for wheelchair users). Lastly, the wayfinding around the boarding platform is non-intuitive to the visually impaired for actual use.

It is also noteworthy to mention the restroom design employed at new facilities, particularly near the Main Media Center, which differ drastically from the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) design standards, evidenced most particularly in grab bar placement. Whether these are poor design choices remains to be judged in future adaptive reuse.

As important as these observations are, I do not wish to leave the reader with an imbalanced view. There exist many successful architectural works in the city. The Krasnaya Polyana Station, by way of example, was truly an excellent architecturally designed facility, the solution accommodated a large population with wide open plazas and large interior spaces, and the wayfinding was excellent as was the signage. One could see the craggy mountains and surrounding hillsides in these architectural solutions. The sequence of movement was well studied and the flow of traffic was successful; one clearly received architecturally designed signals that aided movement from one level to another.

An Opportunity Emerges

With the Olympic and Paralympic games behind us, Russia must now grapple with a grand scheme of adaptive reuse as it develops a new vision for this village. This vision needs to examine how one moves through the site, uses the transportation, walks from building to building, and essentially gains a sense of place. The concept of an accessible path of travel was put in place but seemingly as an afterthought with a variety of interpretations that lacked the consistency we in the western world have come to expect through the use of a model code.

While I was able to watch the vision of Sochi as a venue come to life and witness the fruits of almost a decades’ work unfold, I was left with the lingering feeling that certain critical ingredients were missing. The performances were largely geared for the able-bodied, seemingly touching the disabled as a sidebar. Even the accessible seating provided for disabled members of the press were far from being well-integrated with the general seating.

While I was able to watch the vision of Sochi as a venue come to life and witness the fruits of almost a decades’ work unfold, I was left with the lingering feeling that certain critical ingredients were missing. The performances were largely geared for the able-bodied, seemingly touching the disabled as a sidebar. Even the accessible seating provided for disabled members of the press were far from being well-integrated with the general seating.

The dynamic opening ceremony was called “Breaking the Ice” showing the importance of promoting inclusiveness and changing perceptions in society. But the hanging of the flag was particularly symbolic for me. The one disabled flag carrier remained on the bottom of the elevated level, a half-completed legacy. Now is the time for Russia to reflect back and broaden its horizon as it looks to the future of this world-class venue.

The dynamic opening ceremony was called “Breaking the Ice” showing the importance of promoting inclusiveness and changing perceptions in society. But the hanging of the flag was particularly symbolic for me. The one disabled flag carrier remained on the bottom of the elevated level, a half-completed legacy. Now is the time for Russia to reflect back and broaden its horizon as it looks to the future of this world-class venue.

I am reminded of a passage in the bid prepared for the International Paralympic Committee that captured the vision of what this venue could be:

Enthusiasm, professionalism and inclusiveness will be the hallmarks of Sochi’s effort to stage [the] Paralympic Winter Games in 2014, Games that set new standards of excellence and create a vibrant celebration of sport.

As seen through the lens of Universal Design, access at Sochi must extend beyond elevators, accessible buses and restrooms. If I were to put my finger on one troubling issue it would be the voids in the reality that sprung from the bid that was written in the last decade. This is the essence of the opportunity for Russia. From the perspective of the total useful life of these facilities, the Sochi 2014 Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games represent little more than the blink of an eye. Russia must seize the moment and ensure that the inclusive vision reflected in the original plans comes forth in their adaptive reuse. It is through this kind of diligence that Russia can establish a state-of-the-art city, accessible and open to all.